Research Interests

What fascinates me about our world is how incredibly complex behavior can arise from incredibly simple rules. This is why I’ve chosen nonlinear dynamics as my main area of scientific quest. Nonlinear dynamical systems could very well be the definition of “complex behavior from simple rules”. Similarly, I am fascinated by emergent phenomena, where fundamentally new behaviors arise in a system, behaviors not at all obvious from the behaviors of its individual constituents. Emergence, and its importance in scientific thinking, has been summarized very well the sentence More is Different, popularized by Anderson in the 80s [1]. It certainly is a sentence that I structure my scientific thinking around.

I am active in a broad spectrum of complex systems: from approaching climate conceptually as a whole and understanding its emergent large-scale interactions, to nonlinear timeseries of climate observations and inferring causal linkages from them, to emerging simple behaviors in socioeconomic systems and their agent based modelling, to the dynamics of music performances, and lastly to fundamental nonlinear dynamics theory and methodology. Furthermore, because all of these systems are so fascinating, I also want to share with the world the power to play with them and understand them just as well I do (and hopefully even better). To this end, I am constantly making high-quality scientific software that make analyzing complex systems accessible, and also I am highly involved in education that teaches how to approach complex systems using a practical, hands-on style.

Summary of Current Research

- Conceptual models for clouds-climate interactions

- Emergent chaos in global mean climate

- Multistability in climate and climate models

- Timeseries analysis of climatic observations

- Complex systems methodology and software

- Multistability and global stability analysis

- Practical approach to education

- Dynamics of music performances

Conceptual models for clouds-climate interactions

Clouds and their Cloud Radiative Effects (CREs) are one of the most important parts of the climate system. Furthermore, CREs are notoriously difficult to estimate correctly in Earth System Models (ESMs, complicated billion-lines-of-code constructs that simulate climate accurately). For example, clouds are the largest source of uncertainty in climate sensitivity estimates [2]. It is also suggested that ESMs are over-fitted to the cloudiness of current climate, and hence have trouble correctly representing changes in cloudiness versus warming or from planet to planet.

I believe that to improve our understanding of clouds and climate interactions at a fundamental level, we need conceptual answers on how cloudiness contributes to climatic variability, climate multistability and tipping, and how this interaction changes when changing a component of climate, e.g., greenhouses gases. To obtain conceptual answers, we need conceptual models. That is why my current main research focus is developing conceptual models of clouds+climate. I am developing theories and tools that allow coupling representations of cloudiness in energy balance models, which are the simplest physically motivated models of climate. These cloudy energy balance models can help us test hypotheses of how we believe clouds interact with climate. They are efficient in facilitating understanding of clouds+climate interactions because they have exceptionally high transparency, are cheap to run, are easy to modify, and simple to reason about and physically justify.

Emergent chaos in global mean climate

Weather is the paradigmatic example of chaotic systems. Atmospheric turbulence is a process so complicated, that scientists that develop forecasting models prefer to represent turbulence as a stochastic noise process instead. But even though our planet is so large, with an almost overwhelming amount of chaotic turbulence, climate is in a sense much simpler. Larger and simpler patterns emerge, such as the robust seasonal cycle of most climatic variables. and the more we look into the past, the more of such patterns we see.

Observational evidence shows that most of these patterns seem to be chaotic in nature. For example, hemispherically-mean seasonal cycles of temperature and cloudiness differ from year to year, decadal nonlinear processes such as El Nino Southern Oscillation have global nonperiodic signal, glacial-interglacial oscillations do not have a constant period, and many more. In this sense, “chaos” does not refer to turbulence, but rather to the large-scale dynamical chaos that emerges from the interactions of climatic components in larger scales of space and time. E.g., such chaos is one way to give rise to the different periods of each of the Pleistocene glaciation cycles (such different-period phenomena are common in chaotic models of state reversals).

The question we pose and attempt to solve is: what is the simplest possible configuration of climate interactions that generates emergent chaos in a global scale? Can, e.g., the coupling of cloudiness to the energy balance be a source of emergent deterministic chaos, and does including this chaos make simple models yield more realistic climate variability?

Multistability in climate and climate models

Multistability is an aspect of climate known since the dawn of climate science, and it is a pre-requisite for climate tipping points [4]. Traditionally, multistability in climate has been analysed in terms of conceptual models like those I discussed in the above sections. Recently however, researchers are trying to understand multistability in larger, and more complex models. The question there is: how do you identify multistability in such models with mathematical rigor, and how do you analyse it despite the huge limitations regarding amount of computations you are able to do?

I am currently leading a project collaborating with several modelling groups on addressing these questions. We are develing a methodological pipeline that can:

- Provide a mathematically objective framework for distinguishing attractors (alternative climate states).

- Add robustness to this distinction by utilizing global state space information.

- Show which aspects of the different attractors are the most different, i.e., which climate observables separate the attractors more in their projected state space.

- Include cutting edge optimization techniques to deal with the huge amount of potential climate observables that may be different, or not different, between the different climate attractors

and more. Please contact me if you have/are doing climate simulations with large models with a goal of understanding multistability in climate. I am always looking for more data!

Timeseries analysis of climatic observations

I am interested in applying timeseries analysis techniques to discover connections, and maybe even rules, governing components of the climate system. I am routinely using a combination of methodologies from rigorous statistics and nonlinear timeseries analysis on observational and/or paleoclimate datasets. For example, in a recent paper with Bjorn Stevens, we were able to apply the technique of surrogate timeseries in the curious case of Earth’s hemispheric albedo symmetry [4]. We showed that if some emergent, large-scale mechanism exists that establishes this symmetry, its timescale should be decadal to centurial.

At the moment, I am using nonlinear timeseries analysis and causal timeseries analysis to understand (1) how temperature differences between warm and cold ocean regions behave as the climate system evolves over millennial timescales and (2) what are the causal mesoscale drivers of cloudiness.

Complex systems methodology and software

I don’t really make a distinction between scientific methodology and software development. Just as a methodological advancement may enable understanding a system from a new perspective, just as well a high-quality software may make an analysis more natural, more effortless, hence leading to similar level of breakthroughs. Similarly, a poorly designed software can make all new PhD students waste their first 6 months trying to get a model to run…

Developing both methodologies and software needs creativity, ingenuity and really hard work. Unfortunately, spending time on software is not rewarded by typical “measures of scientific success”, but I am actively advocating for a change on this front.

With a lot of talented people we constitute JuliaDynamics, of which I am the lead developer. There we are developing new software that allow analyzing complex systems with much less effort that ever before. The same software, due their intuitive structure and extendibility, also allow us to create new algorithms that surpass existing ones in both usability, but also performance. The most important aspect of our efforts however, is their openness. We take extra care so that the open source code we write is transparent and accessible.

In my own experience this openness has led to much more collaborations I could think of. For example, our work on Agents.jl, a framework for agent based modelling used for e.g. socioeconomic systems, showed that we have designed something better and simpler than ever before [5]. Other software, such as DynamicalSystems.jl, allowed us to develop a generic algorithm for finding attractors for arbitrary dynamical systems [6]. Such generality would be really difficult to achieve if we were to start from zero, without having a generic library to begin with. I strongly believe that JuliaDynamics is a living example of how scientific algorithms and software quality should not be thought of as independent things.

Multistability and global stability analysis

The main frontier in nonlinear dynamics that my “practical”/methodological/software endeavours focuses on is multistability and global stability analysis. This means analyzing stability of dynamical systems versus non-local (or non-trivial) perturbations as opposed to the traditional continuation bifurcation analysis. This requires having a “birds-eye view”, looking at the state space as a whole, instead of focusing locally in fixed points in the state space. This also requires finding all attractors of a system, as well as their basins, and understanding the shape and size of the basins. This work was kickstarted by what I believe is my most impactful work, our paper on automated global stability analysis [7].

From there, I am trying to understand how basin size and shape changes as attractors lose stability, as well as trying to come up with methods that can estimate global stability of attractors from limited observed data.

Practical approach to education

This section is actually directly tied with the previous one. There are dozens of textbooks on nonlinear dynamics. Oddly enough, none of them represents code sufficiently, while most don’t even talk about it. This is in line with the weird scientific perception that “code is not science” because of even more weird reward system of scientific success.

I believe this should be changed, cut directly from the root. Hence, the best way to change this is by changing how we educate new generations to perceive code and practical aspects. Technology has thankfully advanced enough to allow one to solve complicated problems while writing concise, expressive, high level code. With Ulrich Parlitz we have taken advantage of this progress, and engraved a new perspective into nonlinear dynamics into a new introductory textbook. The textbook is called “Nonlinear Dynamics: an introduction interlaced with code” and is published by Springer-Nature. in the “Undergraduate Lecture Notes in Physics” series. It has a fresh approach that explicitly discusses practical aspects and writing code. You can find more details about the book in this short video presentation.

To give you an idea, here is an excerpt. We show a figure of how the entropy of a chaotic set changes with the partition size. Next to the figure is the full code necessary to reproduce it.

I’m also using this new approach to make accessible public-oriented educational videos such as: Explanation of the butterfly effect and deterministic chaos using billiards

Dynamics of music performances

Music is perhaps the biggest cultural achievement of humanity. But music is also a very complex process. This is because of the huge number of factors involved. Besides the actual music notes themselves, a process at least three dimensional (time, intensity, pitch), there is also human interaction, expression, and improvisation. Yet, what has become clear in recent years, is that the timeseries of human music performances are underlined by seemingly universal mathematical patterns. For example, the timeseries of timing, intensity, and even pitch fluctuations seem to be accurately represented by pink noise processes: they are random, but also with power-law-like temporal correlations. I describe all of these findings in an invited talk I gave at the University of Nottingham, which is available on YouTube.

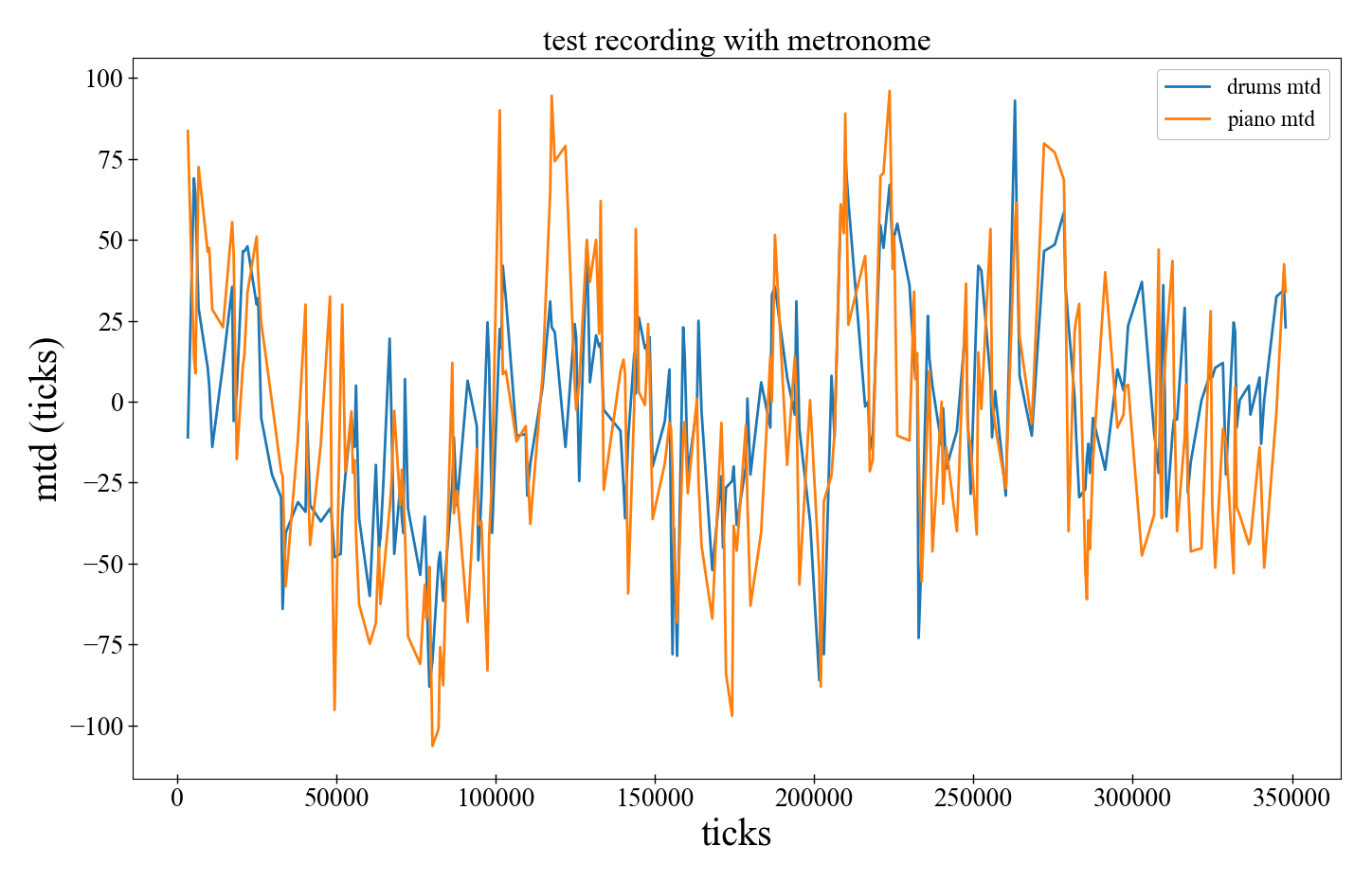

What I am currently interested in is how musicians synchronize. For example, the following plot comes from a recording of “Heard it through the grapevine” that I have played with the keyboard player of my band (see the “Music” page if you are interested). The x-axis is simply time, while the y-axis shows the temporal deviations of the played notes of either drums (blue) or piano (orange).

While these timeseries are in a sense “random” (this pink noise we mentioned above), it is also clear that they are very much correlated on each other. The fluctuations go up and down together, and this happens because the two musicians are “synchronized” with each other. I am currently analyzing the nature of this synchronization, and how it can exist in such a setting, where the timing of the musicians have a stochastic nature. I am also interested in understanding how a metronome affects this synchronization. Musicians generally agree that it is easier to synchronize with each other in the absence of a metronome. From a scientific perspective, the opposite should be true: since the timings of humans are stochastic, having a purely deterministic perfectly periodic signal should make synchronization easier. That’s not the case, but why and how? To answer these questions I perform experiments, recording musicians and then analyzing the recorded timeseries.

References

- Anderson (1972), Science 177, 4047

- Zelinka et al. (2020), Geophys. Res. Lett., 47

- Datseris and Stevens (2021), AGU Advances, 2, e2021AV000440

- McKay et al., Science 2022, Vol 377, Issue 6611

- Datseris et al. (2022), SIMULATION

- Datseris and Wagemakers (2022), Chaos 32, 023104

- Datseris, Rossi, Wagemakers (2023), Chaos 33, 073151